Despite this, its use persisted: in 1620 the Ming emperor Zhu Changluo died after taking the elixir of life, a ‘red pill’.Ĭommon people also pursued immortality. Since the itching and heat were often unbearable, nobles took to wearing loose clothes without underwear and went without bathing for months. As these reactions were taken as a sign that the body was becoming stronger and on the verge of becoming immortal, the elixir was taken more enthusiastically. An appropriate dose was eventually formulated, but, although not everyone immediately died from taking it, they were all poisoned, experiencing symptoms such as dry heat and itching skin. This so-called elixir of life contained mercury sulphide, arsenic sulphide and other toxic substances that often caused death. In the Wei Jin Southern and Northern Dynasties of China, Taoist alchemists developed an elixir of life for nobles, made of eight minerals that were combined, heated, distilled and cooled into a granular powder. The pursuit of immortality was not limited to emperors, however. His death, in 87 BC, revealed that the gambit had not worked. He drank it every morning together with jade that had been ground into powder in order to be as unbroken as jade. The dew from the night air that condensed on the plate was called amrita. According to the chronicle Zi Zhi Tong Jian, in 115 BC Liu Che cast a 20-foot bronze plate to collect dew.

Some scholars believe that he led the children to Japan and settled there, as Japan also has a legend about Xu Fu: Jinnō shōtōki (1339) mentions that a man named Xu Fu came from the Qin Dynasty and, in Shingu, a city on Japan’s eastern coast, there is a tomb and shrine to him.Įven less unsuccessful in the search for the elixir of life was Liu Che, Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty. He sent the alchemist and explorer Xu Fu to lead thousands of children to ask for the elixir of life, but Xu Fu never came back. According to Shi Ji, The Records of the Grand Historian, written in the first century BC, the emperor heard that there were three holy mountains in the sea, named Penglai, Fangzhang and Yingzhou, which were inhabited by gods. Emperor Qin was the first emperor of a unified China in the third century BC. Seeking to prolong this state of affairs, immortality often became their pursuit. This myth is the oldest recorded reference to a dietary supplement in China.Ĭhinese emperors had supreme authority and enjoyed extravagant lifestyles.

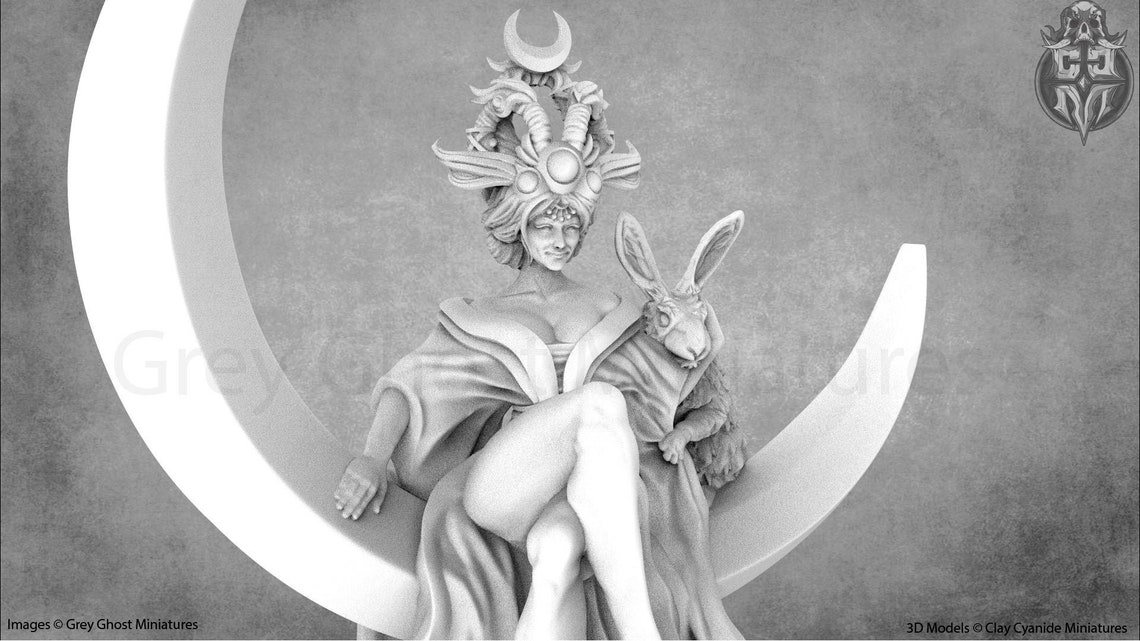

Her body became lighter and lighter and she rose up so high that she flew to the moon, where she has lived ever since. Unable to stop him, Chang’e swallowed it.

However, a man named Pang Meng took advantage of Hou Yi’s absence to attempt to steal the elixir. Granted it, he gave it to his wife, Chang’e. As a reward, he asked the mother goddess Xiwangmu for the elixir of life, which would make the drinker immortal. An archer named Hou Yi shot down nine suns and saved the people. A long time ago, the story goes, there were ten suns in the sky at the same time and the earth was scorched.

The Huai Nanzi, compiled during the early years of the Han Dynasty (202 BC-AD 220), records the myth of Chang’e, who flies to the moon. The name Chang’e is a reference to the elixir of life. In January 2004 the Chinese government announced a lunar exploration plan, the Chang’e Project, which saw the launches of the probes Chang’e 1 to 5, the last of which returned on 17 December 2020 with lunar samples. Modern dietary supplements are the latest iteration of the ancient and longstanding tradition of the elixir of life, which, unlike medicine taken to cure ills, is taken in the belief that it can strengthen health, or even grant immortality. China has become the world’s second largest consumer of dietary supplement products after the United States and is a major importer of supplements: 12.8 per cent of the dietary supplement products produced in the US are exported to China. In 2020 nearly 890,000 new enterprises were established, the largest annual increase yet. The dietary supplement market in China is huge. ‘Putting the miraculous elixir on the tripod’, woodcut from Xingming guizhi (Pointers on Spiritual Nature and Bodily Life), by Yi Zhenren, 1615.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)